ESSAYS

CRYTICAL MYTHOPOEISIS :

(RE)MEMBERING THE FUTURE

by Michael Dudeck

THE OMEN AS BODY OR

THE PLACE OF THE SKULL

by Michael Dudeck

MICHAEL DUDECK

by Meeka Walsh

INTERVIEWS

NUNU THEATER / MICHAEL

ROBERT ENRIGHT

AND MICHAEL DUDECK

BOOKS

PARTHENOGENESIS

2009

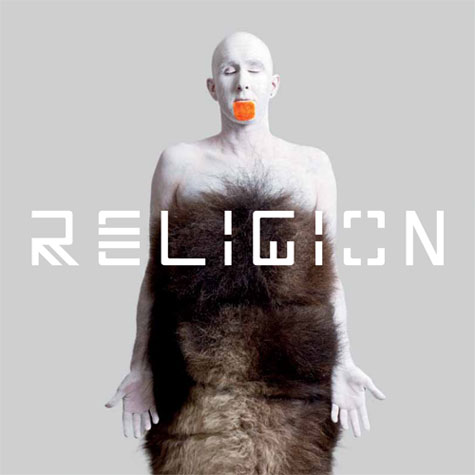

RELIGION

2012

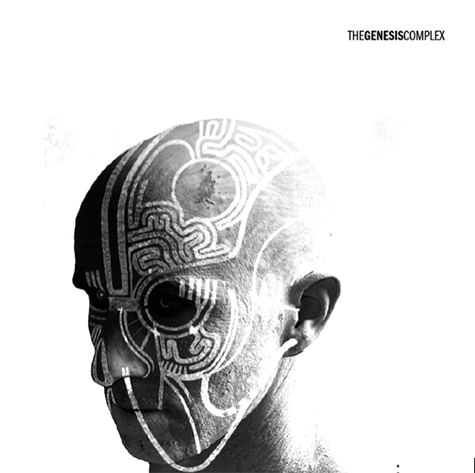

THE GENESIS COMPLEX

2014

CRYTICAL MYTHOPOESIS : (RE)MEMBERING THE FUTURE

CRYTICAL MYTHOPOESIS : (RE)MEMBERING THE FUTURE

by Michael Dudeck

“All living Art is the History of the Future.”

—Wyndham Lewis.

I.

Past and Future are not opposites. They are not separate from one another. They are twins. Not identical, but born from the same Womb.

II.

Past and Future are fictions, constructed out of meditations upon and interpretations around paradigms that we can access only by way of our imaginations. Whereas the past (the was) produces mythologies, documents and artifacts, Futurity (the could be) engages those relics as blueprints for hypothetical structures. The future is a realm wherein imagined possibilities can be constructed, and the past is a construction that lives in perpetual excavation.

III.

Kierkegaard’s proverbial dictum that “Life can only be understood backwards”1 augments our conception of the Past as a place of projected meaning. History is both the fiction of empires and an amalgamation of interpretations of those fictions : commentaries built atop of commentaries forming a hive of symbolic meanings. The authority inscribed upon those who study “History” imbues the artifacts housed in the ark-hives of “the past” with the aura of factuality. This ascribes a critical difference between the imagined past and the imagined future: that which happened before (the was) is bound to a set of established narrative codes maintained by the Canon; whereas that which has not yet happened (the could be) inhabits the precincts of possibility, and therefore, Prophecy.

IV

As a matter of classification, mainstream knowledge and entertainment industries are hardly consistent in their demarcations between Fantasy and Science Fiction. When asked to explain the difference between the two, Isaac Asimov replied that “Science Fiction, given its grounding in Science, is possible;” whereas “fantasy, which has no grounding in reality, is not.”2

V.

“Speculative fiction” emerged as a democratic organizer, containing the sub-genres of Science Fiction, Fantasy, Science Fantasy, Alternative History and Magical Realism. The word ‘speculative’ descends from the Lain “speculum” which literally means “mirror”, from specere which means “to look”. The “mirror” that sci-fi uses on the past, and that fantasy uses on the future, are means by which we can analyze concerns of the present without the weight of historical and contemporary connotations, and literal histories. Speculative narratives utilize recognizable characters and events, but enshrine them within the domain of artifice – thus permitting identification with, and rejection of megalithic moral questions, without the burden of overt geopolitical or philosophical alignments.

VI.

It could be suggested that an inherent division between the binaries of Fantasy/Past and Sci- Fi/Future is that where fantasy looks upon technology and its developments as suspect, Science Fiction embraces and populates its narratives within technologically advanced civilizations.

Magic, Science and/or The Machine are the dominant sources of power in virtually all “speculative” narratives. At first glance one might see The Matrix, and The Lord of the Rings as containing radically different meditations upon the Cyborg3. But as Tolkien unearths, in the opening paragraph of his biblical “Silmarillion” the difference between the mythological ancient/medieval imaginary is not so distinct from that of the space opera :

“the sub-creator wishes to be the Lord and God of his private creation. He will rebel against the laws of the Creator – especially against morality. Both of these (alone or together) will lead to the desire for Power, for making the will more quickly effective, -- and so, to the Machine (or Magic)... The Machine is our more obvious modern form though more closely related to Magic than is usually recognized.”4

VII.

Mythopoesis, christened by Tolkien, is the act of making/creating mythologies. The term mythopoeia descends from Greek μυθοποιία, "myth-making", and was popularized in modernity when Tolkien wrote a poem of that name in 19315. In early uses, it referred to the making of myths in ancient times. This is an altogether different act than the inscription of already established mythologies : mythopoeia is a term reserved for visionaries who imagine an entire set of myths that themselves perform commentary on already existing mythologies.

VIII.

Author of the best-selling Magicians Trilogy, Lev Grossman argues that while 70s and 80s mainstream media was dominated by Science Fiction, a change occurred in the late 90s with the advent of Harry Potter, turning the mainstream speculative consumer from the wormholes and death stars of space to the castles and faeries of the imagined past.

He claims that fantasy is a literature of longing, a longing for things that have been lost. He argues that “most of the history of human literature is a history of fantasy...If you go back before the 18th century, it’s hard to point to anything that would not now be classified as fantasy.”6 He includes Shakespeare (with its’ ghosts and witches), Dante, Homer and Ovid. He claims that the 18th century turned literature to focus upon hyper-realism, which dominated the imaginative spheres until very recently, where the cataclysmic advent of accelerated modernization forced us towards an imaginative reconciliation of our lost, mythic past.

IX.

Conversely, arguably the first work of what we now call Science Fiction is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Whilst the book can be coded as both an extremely contemporary Gothic novel, as well as a work of Horror, it is that sheer possibility that through Science (not magic) we have the ability to create life, and achieve that most ancient of mythological yearnings (to become God) that rightly situates this at the genesis of a new era of literature and of human sovereignty.

Immortality is a theme that unites many disciplines within the speculative genre, and seems to be at the core of the question of whether Science has the power to make us into deities. Although Victor Frankenstein takes early inspiration from occult writings (which codes him as a typical fantasy- Magician) he undertakes “a decisive change of direction when he decides that it is modern science, not ancient magic, that will open the portals of wisdom for scholars of his and future generations.”7

X.

A growing number of Contemporary meaning makers, cultural workers, writers and artists find themselves gravitating towards the language of speculative fiction in order to engage with a host of questions in an increasingly post-human era. AfroFuturism has emerged as a response to the implicit racism in mainstream science fiction, wherein scholars, thinkers and creators of colour have begun to re-imagine an “ancient future” where black characters and ideas are protagonists within their own narratives of sky-walkers and star-people. It also dares to situate the “contemporary revelations about time and metaphysics” in its rightful place : in the teachings of ancient witchdoctors and mystagogues.

Likewise, “Queer Futurity”8 emerges as a theoretical path to imagine a speculative queer future, one that is always in a state of be-coming. Aliens are often depicted as post-gender beings, and in this capacity, have the potential to host utopian propositions which can be teased out and explored in the mediated dimension of literature and Art. Ursula LeGuin’s The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas9, which depicts a world wherein all citizens are polyamorous and live in fruitful collectivity – and yet beneath their seeming actualization of utopic queer futurity, a nagging deformation lies hidden and is ritually protected to maintain the illusion of cohesion. Queer Theory proposes a paradigm with radically different contours, a dissolution of binaries which can create a world as yet not imagined (and by its very nature must inhabit the imaginary, the future).

XI.

What unites those engaged in contemporary speculative practise (ranging from written texts to web-works, virtual art, bio-art, performance, visual art and film) is that we are utilizing these tropes, these narrative strategies critically and conceptually in order to facilitate modes of cultural debate.

Science Fiction and Fantasy both began as contemporary, “of-their time” strategies inhabiting the hearts of the questions they were posing – in relation to past, present and future. Now, established memes, they are systems that can be utilized and manipulated to politically, socially and ethically engage in profound, ongoing moral debates. The world is rife with cataclysmic emergency. Our narratives have all been gathered to help soothe a story, or a myriad of stories, to make meaning in the midst of our greatest fears. Afghani Contemporary artist Lida Abdoul cites :

“Art is always a petition for another world , a momentary shattering of what is comfortable so that we become more sophisticated in reclaiming the present.”10

XII.

Speculative Contemporary Practises, critically grounded and mythologically inclined are blueprints for utopic undertakings, that speak to us and our publics in a language both ancient and otherworldly. We need to seduce our publics into a mode of questioning that is both critical and expansive. Where better to look than to the cults of Imaginary Worlds ?

XIII.

Crytical Mythopoesis unites the speculative genres within a rhizome of critical inquiry.

XIV.

The Revolution will be Stylized.

XV.

Remember the Future.

1 Søren Kierkegaard, Journalen JJ:167 (1843), Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter, Søren Kierkegaard Research Center, Copenhagen, 1997--, volume 18, page 306. 2 Milne, Ira Mark. Literary Movements for Students. Gale, Cengage Learning, 2009, p.144

2 Milne, Ira Mark. Literary Movements for Students. Gale, Cengage Learning, 2009, p.144

3 Haraway, Donna. Simians, Cyborgs and women : the reinvention of nature. New York : Routledge, 1991, Print.

4 Tolkien, JRR. The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Miffin, 1997.

5 Tolkien, JRR. Tree and Leaf. London : Allen & Unwin, 1964.

6 Grossman, Lev. Why Our Culture Looks to Fantasy Novels: Lev Grossman. Online video clip. Youtube. YouTube, March 7, 2012. Accessed : 12 April 2016.

7 Stableford, Brian. Frankenstein and the Origins of Science Fiction, in Anticipations : Essays on Early Science Fiction and its Precursors, ed. David Seed, Syracuse : Syracuse University Press, 1995, p. 46- 57.

8 Munoz, Jose Esteban. Cruising utopia: the then and there of queer futurity. New York : New York University Press, 2009.

9 Bausch, Richard & R.V. Cassel (eds). The Norton Anthology of short fiction. New York : W.W. Norton, 2006.

10 Abdoul, Lida M. Lida Abdul: Feminist Artist Statement. Brooklyn Museum: Elizabeth A Sackler Center for Feminist Art, 2007. Web. 15 Apr. 2016. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/feminist_art_base/lida-abdul

THE OMEN AS BODY OR THE PLACE OF THE SKULL

THE OMEN AS BODY OR THE PLACE OF THE SKULL

by Punc Arkæology (Michael Dudeck)

From The Body as Omen Exhibition Catalogue,

curated by Sheilah Wilson, 2014

In 325 CE, in the midst of Rome’s widespread conversion to Christianity, Emporer Constantine I sent his mother, Helena, on an expedition to Jerusalem to locate relics from popular Christian mythology. Utilizing the Gospels as a guide, she excavated a number of objects from a host of locations she had identified, initiating the Romanized re-appropriation of the Promised Land through the acquisition and appropriation of objects and locations.

Of the many discoveries she made, one of the most prevalent is Golgotha, a site just outside of Jerusalem, where Jesus is said to have been crucified. The word Golgotha, descending from the Aramaic gûlgaltâ translates to Place of the Skull. Etymologically, this may relate to the Aramaic Gol Goatha, which translates to “Mount of Execution”, as well some Christian and Jewish traditions suggest it refers to the location of the “original” Skull of Adam.

In times of conquest, colonizing religions appropriate the spiritual centers of the conquered. When Hadrian conquered Jerusalem in 135 CE, he built a temple to Jupiter overtop of the alleged tomb of Christ. Upon Helena’s arrival, she ordered the temple be demolished and began an excavation of the area which unearthed three buried crosses. In her frantic quest to authorize the artifacts of Constantine’s new religion, she invited a dying woman from Jerusalem to lay hands upon each of these crosses.

According to legend, the first two she touched had no effect on her whatsoever, but when she touched the third she miraculously recovered. The object that transmitted her healing was christened ‘The True Cross’, whose splinters have been distributed across the known world and are to this day worshipped as reliquaries. It is said that Helena also located the nails used in Christ’s crucifixion, and had one placed on Constantine’s helmet and the other in the bridle of his horse.

Many years later, in the 14th century, a burial cloth imbued with the faint impression of a naked man with folded hands across the groin was named The Shroud of Turin and ascribed to have the traces of Christ’s blood-drenched body. Heavy concentrations of blood on both the hands and arms are said to be in accordance with the ‘imprints’ of crucifixion. Forensic tests in the 1970s revealed the alleged bloodstains to be comprised of tempera paint tinted with hematite, but many still believe in the authenticity of the object. It is now housed in Turin, where it is ritually exhibited to the public, with its next presentation slated for 2015.

Sheilah Wilson has organized an exhibition attempting to address “the intertwining of both transcendence and unequivocal placement “ of the body through live performance and performance residue in a gallery space in Queens. Braiding together 6 performances over 3 nights (and including one durational performance over the course of the entire exhibition) Wilson hosts rituals where bodies are inscribed with their practitioner's meanings, and then she immerses herself in how to preserve, edit, curate, de- and re-install the imprints of the bodies that performed.

While the origins of Performance Art are constantly being debated by The Priests of Culture, as a practitioner and a theorist I place its ‘Beginning’ in tandem with the dematerialization of the art object in the radical social, cultural, and political reconfigurations of the 1960s. This early work, distinctly feminist, ephemeral, anti-market and intentionally unpopular barely resembles the highly-commodifed, popular religion known today as ‘Performance Art.’ Thanks to a combination of drastic economic reconfigurations, the rise of prominent new social theories infecting mainstream culture, and what I would argue as a primal hunger for ritual after the death of God, Performance Art and its contagion have together ‘mounted’ the Institutional matrix of Art and spread its seed across a vast swath of unexpected cultural terrains.

By initially relinquishing the materialist and consumerist machinations of art production, early practitioners enacted a radical renegotiation of cultural values, which bears more in common with early religious paradigm shifts than secular audiences are at first inclined to perceive. The Messianic literature of Ancient Israel prophesied a redeemer who was meant to facilitate the end of Rome’s violent Occupation through an early iteration of a Holy War (the word ‘zealous’ descends from the radical political movement in 1st century Judah called Zealotry, of which the infamous betrayer Judas was a core member). Christ’s prophetic ministry, however, advocated a radical re-interpretation of the messianic agenda, proposing spiritual rather than political liberation through a paradigmatic shift in the conception and understanding of God. Christ ‘performed’ this ideology upon a Cross which became an iconic symbol, an artifact charged with the residue from the performance enacted upon it.

Subsequent generations layer interpretations overtop of interpretations of Christ and his teachings, in perfect accordance with a vast lineage of rabbinical commentary. However the Catholic Church also sanctioned a form of commentary through its recognition of images, particulary of the crucifixion to be produced and marveled at. This imaging had always run counter to adherents of Judaism who still clung firm to the second commandment which prohibited the graven image, or anything at all that bore likeness to its referent. The depiction of Christ’s crucifixion has been endlessly reproduced as a symbolic iteration of a theme of sacrifice wherein he offered himself for the world’s salvation. The image of his body, flayed and stretched upon the stage of the cross, has come to viscerally symbolize his ideology; occupying an ambiguous placement between idol and icon.

As Performance Art wafted in and out of mainstream culture, art institutions struggled with how to administer, preserve and integrate this radical new program much in the same way that the Pharisee, and later the Romans attempted to integrate the radical revisions of Christ. Objects that were used in performance began to occupy a similar religiosity as the holy relics, imbued and inscribed with the history of the actions that they helped facilitate. The aura of their maker could be glimpsed through the exhibition of ‘relics’, along with accompanying texts that described their importance.

What I think Wilson is addressing in The Body as Omen is the remnant or the imprint of the body within these objects. By addressing the “body as proposal” I see a very radical and authentic configuration which examines the ‘ideas’ that the body, and the body’s traces, come to symbolize.

Performance theorist Shoshana Fellman writes that “the scandal consists in the fact that the act cannot know what it is doing.” For that reason, a curator of performance cannot necessarily write about the work as they could do with tactile objects who statically perform their ideas, for even if a firm script is written, the ephemeral nature of the medium defies prescription.

Performance Artist Sharon Alward (one of my most esteemed mentors) always said that “an encounter is always more than its description.” The paradox lies in the fact that the encounter, no matter how extensive, is almost always experienced firsthand by a select few. The echoes reproduce in a stream of commentary and appropriation, and live on through objects, and stories about objects, creating the potential for a host of fertile, reproductive interpretations rather than a host of accounts.

In an interview about religion and contemporary culture with Jian Gomeshi, cultural critic Camille Paglia asserted that as a literary scholar, she ‘hears’ through scripture the remnants of an authentic historical Christ. Though she is an atheist she called the messiah “a brilliant performance artist who had incredible epiphanies about reality.” Whether or not ‘he’ ever existed, or even if he truly performed all that he was said to, his embodiment of his ideologies has become an artifact central to the Western identity, particular the fields of Western concepts of Art. Things he is purported to have touched, been bound to, or to have touched him gleam with a supernatural power that believers and non believers alike can attest to.

The Jerusalem Syndrome is the name given for a host of severe religious mental problems which approximately 100 tourists per year experience when they travel to this ancient city. In many cases, psychosis can be triggered just by being near this site of religiosity that is performed and confirmed by the host of highly charged spaces and objects. The fact that this behavior occurs in non-believers and believers alike is evidence to the power that performative religiosity can hold, particularly in the symbols or objects that are left.

The Body as Omen is a site of non-religious, neo-religiosity wherein practitioners undergo acts of ritual sacrifice, offering both their bodies and their ideas to a public for consumption and inscription. This inscription splinters into objects, images and texts which then transform, through an alchemical combination of time, memory and archive fever into artifacts, relics and omens.

MICHAEL DUDECK

MICHAEL DUDECK

By Meeka Walsh

featured in WINNIPEG NOW (2013 Winnipeg Art Gallery Press) pp. 39–42

It begins with Genesis, where most of western culture’s stories do, but Michael Dudeck has a very different originary narrative in mind when he speaks about riffing on the story. It’s not linear with a fixed beginning and an immuatable framework to support it, replete with reinforcing rituals and written laws governing it. The story of Genesis and the book in which it is written has formed the basis for the exclusion of queer and alternately gendered people, so Michael Dudeck has used feminist and queer theory, combined with his antipathy for the prevailing biblical narratives, to begin constructing his own religious stories. Like Shawna Dempsey and Lorri Millan whose work is also included in Winnipeg Now, he found his own image missing from the received stories and set about to rewrite them in a likeness closer to his own. What he had in mind is a form of parthenogenesis where the mythologies can be self generating and open to revisions. His founding myth goes like this, at least for now : It all began in the vast, frozen circumpolar region called Hyperborea. (The book in which this was written is called the Amygdala). First there were two deer figures, Esed and Ura, hermaphroditic creatures who had wandered for eons in Hyperborea. And then there was the Qedishtu, the baboon – brooding, colatile and on occasion dangerous, and also hermaphroditic. The physiology of the deer is complex, and in its variety offered new ways of considering gender, having both long phalluses and many breasts. The baboon has two serpentine phalluses with which he has impregnated the deer. The progeny of this union, the Baculi, became all of mankind. So, in Michael Dudeck’s mythology we have the loss of innocence and the story of the Fall. Not necessarily from grace but into a narrative that includes queer, and in Dudeck’s performative shamanic character, the multi-gendered.

Growing up in a Jewish family it was Old Testament stories he learned. Hearing them, and after when he studied, he found himself less than satisfied with what he perceived as the dismissal of the natural, natural world. In the inclusivity he is seeking in his shaping mythic stories, he says it is necessary for there to be the option for expansiveness, change and self-generation. The static fixed stories make no accommodation for the generative stories he wants as guiding texts, so he’s written his own.

The Qedishtu in Dudeck’s founding garden were far from exemplary. They were, according to the artist, shaman spiritual leaders and cannibals, operated outside of morality, which provided another entry point for rethinking definitions. Dudeck refers to himself as a witch doctor and names as his models and mentors AA Bronson, who has conducted instructive programs, his School for Young Shamans – a master class at the Banff Center, for example, and Joseph Beuys, Quentin Crisp, Oscar Wilde, Walt Whitman and Allen Ginsberg.

Traditionally, religions seek to proselytize and persuade new converts. This doesn’t interest Dudeck for whom religious practice is a way of being in his own person. Neatly ambiguous though, is his inclination to speak of a viral inhabitation in the form of a media virus as an infiltrating agent. Infecting in this way is his form of resisting the dominance of the heternormative structural princples that have simply excluded so many, aware at the same time of the implications in queer history, of a viral reference.

Dudeck’s work has been largely performance-based. For Winnipeg Now, he was working in a major gallery and had chosen to present his work as though it were a museological installation. It was a form of archaeology that allowed him to present his own cosmogony. He has published a small book titled Religion (2012), which is both an outline of the order’s matriarchy/patriarchy and its three founding figures, and an explanation of his mutating doctrinal theses. There were two large inkjet prints on ragpaper titled Messiah (untainted) (2011) and Messiah (and s/he will be crowned with laurels in oblivion) (2011), which is a worked version of the first print, bearing Dudeck’s surface incisions on this presiding figure who appears to be in a trance-like state of consciousness, or who may have moved beyond to another realm entirely. Messiah (the Remnant) (2012) is a little larger than a human figure – the mummified, wrapped remains in museological presentation protected from access by a Plexiglass sarcophagus that makes the figure both spectral and specimen for museum study. Michael Dudeck’s visual treatment of this figure is a kind of steampunk aesthetic. The figure is wrapped and draped in layers of deer hide, plaster, plastic hosing and tree branches, and the poured plaster has pooled, dripped and discoloured, lending it archaeological credibility. The two deer figures are life-sized, Ura and Esed, and are built on taxidermy forms layered and assembled from deerk skin, coral, bone, glue and overlayers of plaster and paint. The intention was that they are at once vulnerable and potent, with their matte white surfaces and antlers and noses painted in a startling orange. They stand on low plinths, unprotected from scrutiny but vigilant and poised to flee. Glowering at them across the gallery is the baboon with his malevolent energy. He is on a raised plinth and secured under a plexiglass box. This presentation of hybrid archaeology – museum placement and trappings aside – is an accurate material reflection of the inquiries into alternate governing myths and principles in which Dudeck is engaged. “I’m guarding deeply the not-knowing” is what he says, open-ended and replete with possibilities.

NUNU THEATER / MICHAEL

A CONVERSATION BETWEEN NUNU THEATER/MICHAEL

Case of Emergency: Emergent Writings on Live Art and Performance,

David Rankovich, Hannnah Maria, Gullichsen, Veli Von Nissinen & Diana Soria Hernandez (eds)

University of the Arts Helsinki Press, pp. 105–108

NuNu: We – Nu Nu – feel close to your idea of invented and un-authorized institution, which is how you define your Museum. We do things in very different ways – you and us – very different, yet there's a lot we might have in common, we believe. Your institution shares with our CASL (Centre for Actors in a Second Language) the imagined, the 'hoping for' trait. CASL – CASTLE is a place where actors in a second language imaginarily retreat, exist and fulfil their potential. Like the Museum, CASL seeks to subvert the Grand Narrative of Real-ism in theatre, which teaches us that characters/actors/performers have nationality, history, biography.

Museum of Artificial Histories and CASL are imagined to be INTERSTITIAL PLACES that really have a contour. Their initiators believe that they can really illuminate those places of somewhere in-between the wish to undermine the dichotomy real – artificial and the nostalgia of wanting to be – just be. The creators of the two institutions are hopeful to give a shape to what tantalises us as being un-shape-able: that undistinguishable moment of passage from the 'authentic' reality to its (most probably) concomitant leap into a hyper-real-ised production of itself.

We like the fact that you lecture. Your lectures in the naked bare similarities perhaps to our lectures about how theatre feels like dead in us. Your nakedness is a different kind of explaining, of arguing your argument. Now – when we are writing – we look at your tape round your arm in a still of your video for Artificial Mother. The tape round your arm is part of the lecture in the same way we talk about how you have to feel that theatre has died in you before even start thinking of working in theatre. Your app for dominant languages and your 'fairly believable digital voice' is not far from our trying to fool ourselves and the audience that we could actually be perceived/received on the same level with the 'native' actors.

MICHAEL DUDECK: I am interested in the way that your imaginary institution also functions (in what I have interpreted) as an imaginary space or place (i.e. an "imaginary retreat"). For me, I am interested in subverting the idea of a Museum, so often associated with a physical space that stores material objects, as an abstraction, an "imaginary" space for encounter... therefore, though it is tempting to imagine what a large-scale 5 story Museum of Artificial Histories would look like ‹and where it would be based, and what kinds of collections it would host› I think it is far more pertinent, even URGENT for me to embrace the idea of the Museum as wholly virtual, a mental projection, even the Museum as "performance" (and the questions of how a Museum can be performed). Andrea Fraser has done some incredible work on this regard. But when you speak of "imaginary retreats" where people can "exist and fulfill their potential" you are relating your fiction to a structure, an imagined time and place that occupies "duration". Can you explain, or explore, or depict what kind of encounter this retreat can be ? And how you conceive of fulfilling one's potential ? This is very interesting language, often used by organizations that have a pre-destined concept of what one's potential is and can be... And what does an imaginary "retreat" look like ? Do you actualize this in material reality or does it maintain itself as abstraction ? Could I undergo a Retreat ?

NN: You could definitely undergo such a retreat – the instant you decide to perform using a second (non-native) language. The place is imaginary in the sense that it is contained somewhere within the distance between the aspiration (of the actor) for a sense of artistic fulfilment/plenitude in that particular performance act and the physical limitations of such aspirations (which in our case is the mastery of language in performance). This place/this locality does entertain a rapport with some form of structured mode. However, the time and place that support the structuring mode are very concrete - they relate to the actor's body (mainly to the enunciation, verbal flux and uttering) as place of occurrence and to the time of the performance principally (as that is the time when the 'retreat' is in an 'active', transformative or operational mode).

The actor's body, tongue, breath, articulation, etc. help give physical dimension to the 'retreat' – both in performance and outside of it. The existence of this retreat is fully dependant on the actor's physical existence/being – the retreat therefore cannot exist (or pertain structure but according to the internality of that particular actor. For every actor the retreat will be structured differently.

CASL is the place where we would like to ideally gather traces of these retreats – memories of them, tellings of them, examples of them. Therefore, CASL should look like a very intimate mapping – or radiography – of individual retreats.

MD: You speak of characters/actors/performers without nationality/history/biography. This illuminates another unique problem of the Museum. In order to mimic, or explore the space of "authorized knowledge" I have invented authorized experts, and constructed an entire Museum staff with a range of knowledge expertise that differs with and queers dominant models/wings of the Museum such as: The Messiah Complex

NN: We are fully aware that characters/actors/performers without nationality/history or biography may not become accomplished in the grand narrative as you see it. They are indeed products of lab experiments, theatrical experiments, imaginative/utopian projects and so on. This problematic is proving quite tricky, particularly in the West and particularly in the context of Intercultural theatre production. The formulas used by the famous architects of Interculturalism in theatre – Brook, Barba or Mnouchkine are the best examples perhaps – have proved very problematic. They did encourage the creation of nationless, history-less, and biography-less characters (and by extension actors), however their fundamental fault has been in their approach. They have undertaken the very hard task of creating (which equates with giving materiality) to such actors and characters via a directorial (therefore an overly narrational) approach, considering therefore the spectacle before the actor/performer, who is ontically at the base of spectacle. As a result, they have had to produce theatrical constructions that very much depicted and claimed to be a theatrum mundi – inevitably a subsidiary playing out of the political, economic, social, artistic tensions and imbalances on the Globe.

We instead focus on the actor as potential generator of nation-ness, history-less, etc. Not fully in a practical, material sense though. But in as much as favourable contexts (text, audience, location, etc.) may encourage an avoidance of such criteria and narratives. Therefore, the creation of nation-less, history-less and biography-less is a moment of complicity between actor and its audience leading to the temporary and mutual suspension of such conventions: we forget who we are (actors) and we forget who we are (audience). This all depends on a willingness to reach this point of suspension but also on very concrete factors (social transformations in a certain community for example) This moment of suspension of belief/narrative is the one which crucially defines 'one's potential' as a second language actor.

MD: The word Interstice is one of great importance to me and my work. My entire trajectory seeks to occupy an in-between space, but by occupying it and marking it as a space it partially loses its interstitial nature... This is an important problem for me. As soon as we name it, part of its' autonomy dies. Hakim Bey's concept of the Temporary Autonomous Zone is perhaps important here... it is an autonomous space that can only be actualized in temporality : as soon as it becomes solid, or concrete, or formed, it loses at least a portion of the fire of it's inception. It is the ritual task of the "Revolution" to take all manner of existing, dominant systems and disrupt them in a chaotic upheaval : throwing things to and fro, thus birthing new problems and new systems and new hybrids. Often within these fires of rapid and insurmountable change, dominant "institutions" are destroyed, "idols" are recognized, deemed false, and massacred, and then after the dust has settled, "NEW" institutions come to take the place of the old ones. As a side note, it is incredibly interesting that new religions when colonizing old ones, historically, most often appropriate the temples of the old religion and update them with the new iconography and precepts. Therefore, as we undoubtedly share a fascination with the "un-shape-able" we both, in our respective projects, do in some ways "give shape" to this mutating hybrid by naming, and institutionalizing it... For me, Queer Theory is especially helpful here, because it occupies a positionally within the rubric of dominant ideology (i.e it is authorized by academic and cultural institutions) and yet by its very nature it defies categorization and definition. In that way I believe it occupies its interstitial nature and attempts to maintain its' mutating hybridity and constant temporality. A relevant quotation from theorist Shoshana Felman: "The scandal consists in the fact that the act cannot know what it is doing". How do you react to/respond to the problem of shaping the un-shapeable ? as a performative and political act ??

NN: It has never been our aim to shape the un-shapable. Not because we do not believe that such an act may be possible (although this should be reason for further meditation) but because we do feel that by trying to do such a thing we would almost surely deny ourselves that state/frame of mind in which you really are (or can be) capable of contact with this 'un-shapable'. From a performative point of view, we believe that there is not much to be done in the direction of giving shape to the un-shapable: the crevasse in the perception/recepation of language by the audience begins existing with the simple utterance. Therefore the un-shapeable is already there – in our tongues that are wrongly (from the point of view of the native) twisting and phoneme-ing. Theoretically, there is no other political and performative structuring that needs to be done, we believe. We put on stage Hamlet for example: theoretically there is no political or performative structuring/shaping needed to be done – second language will do it for us! Any eventual structuring that might need to follow – so that as to aesthetically sustain such a powerful and well-known text – is only in line with the audience's expectations and how you imagine or want that audience to be. When you have started to speak Hamlet in English as a second language a political and performative shaping has already started and it encapsulates the shaping done by all the individual actors/tongues of the performance. Hamlet c'est moi! That is enough to say if you're an actor in a second language. The mistake that Brook and all the others I have mentioned did was perhaps that they were directors.

MD: I am very interested in your quotation that "you have to feel that theatre has died in you before you even star thinking of working in theatre". This is fascinating, because I believe I always knew that theatre was dead... Despite a predilection towards "the stage" I chose the disciplinary path of "visual arts" and almost immediately began to gravitate towards the "performative" dimensions of that space. Though performance art and theatre have many crossovers, I think I aligned to my "disciplinary categorization" because I wasn't interested in the illusion language of dominant cultural performativity (i found the theatrical conventions and spaces to be entirely pre-meditated and scripted. As a visual artist I was trained to examine every object and every environment as essential ingredients to the meaning of the work (i.e. how its made is what it means). I resisted any overt relationship to the stage (an elevated platform) the audience (seating to create passivity in audience) and space (the theatrical infrastructure i.e. lighting, set, acts, effects)... Now, however, I am occupying and exploring these dynamics in the same way a sculptor explores meaning-laden objects (such as flags, weapons, animals, etc.). And increasingly I have been working at the intersection between theatre and live art, inevitably having to work within these pre-scripted environments, however coming at it with a different perspective. I wonder if you can elaborate upon the "death of theatre" and articulate what has, if anything, taken its place, or, alternately, how its trajectory is shifting after its ritual death ? Does your work, or my work, or the work of other practitioners who have acknowledged this death, participate in a sort of "ritual resurrection" ? Or are we simply creating effigies of what theatre, and the theatrical impulse once was ??

NN: We believe that we are all more or less involuntary priests at various altars, albeit some of us play the roles of contesters or denouncers (as you might do, perhaps) of theatre's insufficiency and insolvency as a form. Us, on the other hand, say that theatre has to die for us, since we see ourselves as custodians of defunct theatrical elements only. We are not saying that theatre has died as a form (although that can be argued by many and quite convincingly) but we feel that we cannot exit our sort of pre-destined function of mortuary workers in theatre. Our only task is to deal with the dead bits of theatre (older or younger) – we are somehow artistically disabled. We do not work with the 'living' theatre, as we are impotent to do so. We acknowledge the fact that there might be 'living' theatre somewhere. We are actually sure there is. But if the world of theatre would be a huge hospital, we are working exclusively in the autopsy room, with the cadavers. We have a separate entry and we never get to see the patients 'alive'. So much so, that we've grown to believe that all patients are cadavers. Perhaps one day we will wake up from this illusion (if it is one). The fear is that 'living' theatre for us would then be a completely foreign land, in which we would be too old and mechanised in our death procedures to be able to exist anew. Whether we are creating effigies or not, is a mystery – we can only hope that one day we will come out of the autopsy room.

Could you detail the relation you envisage between artificial and fictional with regards to the Museum? We, as theatre makers, tend to see artificiality from a point of view of the concordance or non-concordance within a certain framework of belief (be it a story, character, etc.). How is an artificial history developed and what is the role of fiction in such a project?

MD: “Artificial” is a crucial term for my work and for the entire project of re-examining history. The Oxford Dictionary defines Artifice as “Made or produced by human beings rather than occurring naturally, especially as a copy of something natural.” This proposes interesting problems, particularly in the dimensions of “natural history”, and spawning outwards to archaeology, anthropology and the study of “history” itself. As soon as “objects” are taken out of either the natural world (i.e the skins of animals or the buried remnants of an ancient civilization) they undergo “museological makeovers” utilizing highly advanced technology to slow “natural” decay and to highlight or animate particular, canonized interpretations which are then stylistically imposed utilizing the museological aesthetic. Then, layers upon layers of complex scholarly research is compacted utilizing a whole other set of devices, into short, easy, accessible “factual” information. The public then experiences the theatricality of the object and its’ history in an almost identical fashion to seeing an epic Hollywood historical film : except the difference is the Museological presentation is somewhow deemed legitimate because, predominantly, “historically” a group of “qualified” white males have “approved” this history. By utilizing the same mechanical and stylistic alchemical procedures that Museums do, The Museum of Artificial History imbues “fake” historical objects with the same aura that “real” objects are permitted, this calling into question the inherent fiction of all authorized information.

NN: What is the relation between the hyper-real (synthetic) and the 'genuine' played out by the Museum? Is there a direct interest to uncover for us how mythologies become histories (and inherently the politics of this transformational process)? Or is it that the Museum remains concerned only with showing alternative ways in which to ingest knowledge? If so, what do you think the Museum's long term impact might be?

MD: The Museum resists any inherent claim for any history, or artifact, or mythology to be inherently genuine. Ingenuity is the Art of making things appear genuine. This is the stylistic alchemy I refer to in the previous response. Perhaps the most important long-term goal of the Museum is contained within its mandate to PLURALIZE the process of History. Therefore, its aims are to “attempt” to contain multiple histories, contradictory histories, imbuing all of these histories with the same authoritative aesthetic, and proposing a model wherein Museum ‘exhibitions’ become active sites of contestation rather than affirmative “glass coffins” of a single pre-selected idea. Mythologies and Histories are constantly mutating, and the Museum seeks to be a site of encounter wherein the performance of the shedding of skins happens live, ritually and regularly, and where the skins, after being shed, are collected and interpreted in a variety of means. If I were to envisage the long-term “impact” of the project it would be, perhaps, to maintain a site of Authorized Contestation, wherein the arguments never settle but continue in a sort of ideological “open source” format (ad infinitum).

NN: You seem to refuse to the Museum an outright institutional face. You seem to prefer to keep it in the realm of playing/realising fictions and artificialities with the scope of dismembering Dominant Narratives. You however do not propose any post-dismemberment ways ahead. Is this a particular political statement? Who do you think will pick up the pieces after what you have dismembered? Will these pieces be located in a Museum, as artefacts, remnants or will it be down to you again to reorganise these pieces in a new narrative?

MD: Yes, perhaps it is political and ideological as well. I think “picking up the pieces” is the inherent ideological assumption I am working actively against. Because “picking up the pieces” implies that the broken shards all emanated from some original source, some sort of “genuine” original that was Big-Banged into a thousand pieces… In almost all cases the dismembering reveals the thousands upon thousands of strategic editorial choices made to create the illusion of a “genuine” original... therefore, I think of the Museum as an on-going, endless excavation. I believe, in order to maintain criticality whilst immersing oneself within The Alexandrian Library of Grand Narratives that have infected, infiltrated and dominated the “Human Story”, one must see the process as permanently dismembered, we must learn to become comfortable with contradiction, multiplicity and the endless array of problems that happen when the past (and its’ traumas) are unearthed. In this light, The Museum also holds the potential to be a Hospital, and a Long-Term-Care Facility for the Wounds and Ironies of History: where cultural workers and publics come to care for and be cared for by the custodians of Knowledge. The origin of the word curator comes from “to care for”: this is fruitful for me, as it holds the potential to unearth the holistic aspects of this somewhat aggressive Social, Political and Historical Intervention.

ROBERT ENRIGHT AND MICHAEL DUDECK

MICHAEL DUDECK

Interview between Robert Enright and Michael Dudeck, featured in WINNIPEG NOW (2013 Winnipeg Art Gallery Press), pp. 131-142

ROBERT ENRIGHT : The big question is the source of the cosmogony and how you determined its scale.

MICHAEL DUDECK : I’m riffing off Genesis. I was adopted into a Jewish family and grew up surrounded by Judaism, so my main origin myth was Genesis. But two things about it were a problem : I was never comfortable with the depiction of animals and Nature in the Old Testament; it didn’t really honour or explore them to the extent that I needed. And there was complete queer invisibility. It’s pretty common practice to return to your initial philosophy, so that’s what I came back to. I have a lot of characters and motifs from that source, which I’m trying to bend and twist so they become more malleable.

RE: Were you conscious of finding different theoretical approaches for the narratives you were setting up?

MD: I think I’ve been building that narrative for the last 10 years. In a way, I’ve been creating my own religion since I started making art. And through experimentation I’ve utilized a bunch of focal points : queer and feminist theory, and a more abstract, raw, visual performative ritual. It’s only in the last few years that I’ve started to organize all those radically different offsets into a larger image.

RE: You take parthenogenesis and use it as an organizing principle.

MD: Yes. When you look at the Old Testament, Adam and Eve are spun from God. In my version, they come from somewhere else. The self-generated beginning is part of an endless process. To accommodate my mythology’s openness to change, I take a lot of language from science because scientists analyze Nature’s endless capacity to destroy, re-create and self-regenerate. Its’ a particularly human notion to create a clear beginning and a clear ending. In Nature nothing begins or ends. Its always shifting and mutating and changing. I’m trying to utilize the language and the framework I was given and slowly insert all the things about it that were missing and that didn’t make sense.

RE: Were you conscious that you needed a generative narrative; so the baboon as to impregnate the two deer?

MD: I was never intentionally constructing a narrative. I was absorbing the imagery. Those two deer have been physically beside my bed for about 10 years. It’s almost like my own spiritual iconography. I have a relationship with the animal, I create my own prayer system. Then, through dreams and through imagery this baboon appeared. In processing material from my psyche, I realized it was possible to project back to the narrative I was given but to put in everything I’ve since absorbed by reading and living.

RE: Carl Jung would go further and say its’ not just your narrative, that is part of the collective unconscious

MD: I’m exploring that much larger narrative of the human psyche right now with my own work. I definitely tape into the idea that you live your life in relation to these mythic stories. But a lot of queer people, myself included, are saying that the stories don’t actually work for us. What would happen if we grew up with different stories, with more complicated stories, or with stories that never solidified? Were’ never one thing. We’re always changing.

RE: You talk about genderedness, so its male and female. Even in your witch doctor conception, the witch is female the doctor is male. Do you consciously think in binary terms?

MD: I’m trying to undo binary thinking but I think there’s no way around its inheritance. I know it’s strange to say, but I’ve got to admit that I also strive not to make too much sense in my work. Otherwise, it’s stifling. One of the things I’ve allowed myself is a platform to constantly shoot out. This is a long-term project and the undoing of binary thinking and its dualistic underpinning is a really long process. I’m working with what it means to be multi-gendered or a new gender being.

RE: How do you determine what transformations your eclectic range of creatures go through ? Why do the deer take the form they take ? Why does your baboon look the way it looks ? I’m interested in knowing what determines the nature of the iconography?

MD: On some level I’m interested in animals that are a cross between predator and prey, which is another binary. I feel the baboon functioning as a decoy for the snake. Baboon’s have really strange habits; they howl at the moon like wolves, and in Egyptian iconography they’re linked with the moon. They exist in this paradoxical realm; people encounter them on safaris and they’re playful but then they tear the roof off the top of your car. I react somewhat instinctively to images. Deer have been prevalent in my own process for a long time and I have this vision of people riding on their backs. I’m trying to modify our perception of these individual creatures. The idea of a deer being a hermaphroditic parent to the human species takes them out of the realm of dumb prey animal with which we’re completely over-saturated.

RE: Your baboon is a member of the shaman priesthood class, but they’re also cannibals. And they’re destructive. Are you simply extrapolating how we see the baboon in Nature?

MD: No, I think it’s a bit of an unconscious association on my part. Traditionally, the idea is that shamanism itself was beyond morality. It couldn’t exist within an ethical framework. If you research the transition from shaman to priest, the shaman was a half-crazy individual and most people feared them. This is from accumulated research and speculation, but my impression is that you actually only approached a shaman when you absolutely needed to because they were in and out of trance states; they were living in this completely insurmountable “in-between”. If you went to them they might cure you but they might just as easily do something crazy.

RE: So that’s what AA Bronson means when he says that the shaman and the artist are close to the criminal?

MD: A psychopath, yes. But then AA adds that we also have extreme empathy and compassion.

RE: How much has queer theory helped you in the construction of this world?

MD: I think that tapping into queer history is an endlessly circular process. I was really close to the work of Ginsberg. Maybe I’m susceptible to religious fanaticism but Ginsberg was all I needed. I lived and breathed everything he did. Then when I met AA (Bronson) I felt he was this other version, and now I’m about to work with Evergon, another bearded homo leader. But in many ways my knowledge of queer theory is hyper-limited. My knowledge of it is experiential. Five years ago I didn’t even organize all this as queer. It was just this religious shamanistic thing I was doing and I happened to be queer. Then they world started to tell me how queer it was. And there is no gay history. It’s a really dark, dingy, archaeological dig that you have to find yourself.

RE: You talk about your religion as a virus that infects the heterogenous world. IS there a danger in using that kind of language precisely because of its connection to the history of disease?

MD: There is an inherent danger and to be honest I don’t really care how its digested on the larger scale. As long as it starts to enter the psyche of the public. ON a really base level, I’m trying to put Nature, queerness and religion in the same space and see what happens when they react against eachother.

RE: When you say that your religion has gone through its first phase, what has been the achievement?

MD: The first phase has been about three years. Artistically, I was flying by the seat of my pants. I’m a young artist, so I was saying yes to everything, and that helped me not think about what I was doing. My choice was t continuously put things in the public realm. It was raw and visceral and perforamtive. Very bodily. I would almost say it was a trance. And the performances were hyper-trance. This installation in Winnipeg Now is my first move into a museological format of artifact and display. It’s a more cerebral examination of the idea I’ve been developing. But the idea itself had to come out in the raw, bloody way, like a child. I think the first three years were really a mess.

RE: Lets talk about the place that performance, language and the book play in the work.

MD: The shaman was really helpful for me because it tied into the idea of being a postmodern artist. Shamans actually did multiple tasks and when I look at my role as an artist, it also involves many things. The performance work was about creating ritual in contemporary culture and tapping into the hunger for that because people flocked to my performances. I think my generation is without religion. We don’t have that as an organizing principle, I started to realize that art is the replacement and that galleries are temples. In every performance something radically unthought of occurs. I don’t feel its completely me running the show. I’m controlling an energy. And I learnt a lot from Marina Abramovic. She said, “You are a vehicle, a conduit that controls that energy. But if you tap into it, it comes through you.” I create the environment, I create the aesthetic, I create the dimensions and I control when it starts and when it stops, and how it shifts. But I also allow a certain amount of intangible material to come through.

RE: If occurred to me in going through Parthenogenesis that one of the stages your system has gone through is to move form being a religion of performance to a religion of the book.

MD: I’m glad you observed that. The transition from shaman to priest is something I’ve researched very carefully because, as I mentioned, the shaman was half-crazy and completely experiential. As an artist I have no choice but to be sober. I have to put things into words; I have to provide information. I’ve had to make that transition.

RE: You believe that a world in which hetero-normativity disappeared would be a better world. Your commitment to that make me wonder if you’re interested in proselytization or conversion?

MD: I think not. That’s another way in which the art world can hold all my contradictions. I think artists are allowed to create a universe around themselves and generate an audience of people that are interested in simply observing that universe. I want to represent this ideology and I think I have the capacity to do it. But my idea would never be for people to emulate my religion. The idea that I’m even calling it a religion is absurd. Its not a religion, its my own system of beliefs.

RE: In your drawing, do you know what the image will be before you start?

MD: I find it in the making. The narrative is constructed in the making, too. I might move in the right direction and create a certain angular thing, which symbolizes some sort of rupture, and then I transcribe that into narration. But not until I have to; I try and keep it floating as long as I can.

RE: I have a sense that anyone sitting in on this conversation would want to know how much of what you’re saying is committed belief and how much is an aspect of performance. They would recognize that you have constructed a persona inside of which you operate. Play may be the methodology, but the larger question centres on some measure, like authenticity. What if you’re pulling the wool over our cultural eyes ? What if you’re the trickster as opposed to the shaman?

MD: AA Bronson talks about the “sham” in “shaman”. My goal is to have those questions asked. There are always people who need proof, who need to know this or that. Spiritual leaders often don’t satisfy the logic of people who want those kinds of answers. But I’m not trying to prove anything; I’m just trying to do it. That’s the thing about being an artist: it grants me permission. I might be naïve, but I’m actually working really hard to keep the naivete.

RE: So it’s actually an epistemology of not knowing, an inverse epistemology?

MD: That’s right. And I am guarding so deeply the not-knowing.

RE: It occurs to me that the homophone of pray is prey. In your cosmogony the two words have synthetic relationship. The violence of religious possibility allows you to be the bird of prey and also the bird of praying. The ambiguities of language will encompass the contradictory drift that seems to engage you.

MD: I’d actually never thought of those two words in relation to one another. I think this project is a strange fusion. Being a witch is a highly active process. You’re not praying or asking or begging for something to happen in your life. You’re actually saying “I’m going to command it, I’m going to make ti happen.” That’s what a predator does. A predator goes for prey. But I’m also drawn to certain aspects of the submissive, un-active principle. I’m drawn to see what happens in those submissive places of prayer. There’s a profound delicacy in it that I don’t understand. Maybe that’s another reason why I’m drawn to the book and to the recitation of the text, and why I’m drawn to an engagement with the sterility of contemporary institutions. Because when you’re not fighting all the time, you can zoom into a softer, reflective process and perhaps you can channel the same energy and create the same thing.

RE: At a certain stage the subject, if he or she repeats things often enough, becomes less a supplicant than a symbol of authority.

MD: That’s right. Reiteration. If you think of an artist like On Kawara you recognize that his idea of constant repetition is an access point. And Marina’s tradition of daily ritual, repetition and order is a way to ground yourself in a spiritual rhythm. It’s a different access point and really contradictory to my instinctive access point, which is ferocious and intense. But that might be my binary interplay. Starting out as a young artist I was pushing all my energy forward and now having earned this space, maybe its’t ime to pull back, go into the temple and reflect.

RE: I want to ask about another of the figures in your cosmogony. Why does the figure under plexiglass take the form it does? I’m not entirely sure which pronoun to use.

MD:

RE: And what about its aesthetic dimension? I’m thinking of Joseph Bueys, the embryonic shaman, having to be wrapped to be saved.

MD: That’s true. Actually I hadn’t put that together.

RE: How would you describe your aesthetic?

MD: Right now the aesthetic I’m working in is sort of punk. That’s partially because of whats obtainable and what’s accessible. So I use Styrofoam base with plaster and clay and rope and sinew and some animal hide. Then everything is coated byt when I put it all together I struggle with whether or not I should clean it up. When we see Greek sculpture we’re used to an aesthetic of the broken and the appearance of all white. At the time they were created they were neither white nor broken, and they didn’t have any fetish attraction. My instinct with this museological thing is to keep all the blemishes; clean them up to a certain extent, but keep that archaeological look beause it locks things in at a certain moment. Later on, I may want to do some hyper-real work with them and create a very different aesthetic and a very different design. But because we’re dealing with cosmogony and origin in this work, I want it to look like some of the artifacts I saw in the Jerusalem Museum. But instead of yellowing mine are white.

RE: So its an aesthetic of punk archaeology?

MD: Exactly. It’s punk archaeology because you’re inventing it as you do it.

PARTHENOGENESIS

PARTHENOGENESIS

Self published, hardcover, 198 pages

2009

Book Launch/Art Metropole

(Edition of 100 numbered copies)

Parthenogenesis exposes the battleground between archaic dualities. Symmetry and proportion wage war against annihilation and the visceral. Ritual practice and mystical questions attempt to regulate an inner barbarity that threatens to strangle and destroy. The Eden myth is resurrected and explored as an archetypal division; what constitutes each aspect? Much of the text in Parthenogenesis comes from the artist himself, but interspersed throughout the work are the words of over thirty thinkers/artist/writers exploring the same archaic divide.

This artist's book is an attempt to map out the conceptual and poetic terrain of Dudeck's large-scale Parthenogenesis performance/installation, a trans-disciplinary production merging drawing, sculpture, video, performance, installation, sound and text.

Available for purchase at : Art Metropole (CANADA) : http://artmetropole.com/shop/8663 Printed Matter (USA) : https://printedmatter.org/catalog/25748

RELIGION

RELIGION

Self-published, softcover, 80 pages

2012

Book Launch : Winnipeg Art Gallery [BOOK]

Edition of 500 copies

Available for purchase at : http://shop.plugin.org/products/religion

“Two white, hairless, hermaphroditic deer emerge upon the badlands of Hyperborea, exiles from another land, devoid of memory. For a thousand years they wander the reaches of the Hyperborean North. They meet an exiled Baboon priest, who enacts sacrilege by inseminating them both, giving rise to a new species of hominids. Characterized by multiple breasts and a large snake-like phallus [baculum] the hominids spread their seed and multiply. At a critical point, a prophet of one gender, marked with orange below his lips, will introduce the written language to the Baculi hominids. Centuries later, after several wars erupt in his name, he will be ritually sacrificed, encased in a tomb, and the epoch of hominid sovereignty will erupt.”

- excerpt from The Book of Qedishtu Prophecies, 2:3

THE GENESIS COMPLEX

THE GENESIS COMPLEX

Self-published, softcover, 80 pages

8” x 8” [BOOK]

2014

Dominant ideologies utilize mythological motifs as a means by which to construct normative behavioral patterns in large populations. The Myth of Adam, Eve and the Serpent, arguably the most influential origin myth of the Western world, has been utilized to regulate hetero-normative coupling patterns and to justify global patriarchy in response to Eve’s temptation as the cause of ‘Original Sin’. Occupying an ambiguous positionality between myth and socially sanctioned allegory, the Eden story has retained a gripping metaphorical pull since it was first inscribed. The Genesis Complex performs a queer excavation of this myth and its accompanying mythologies by unsettling assumptions surrounding the household narrative, whilst exposing a range of interpretations that have permeated the public and political spheres. The apparatus behind the myth is exposed and new queer readings are provided which illustrate the promiscuous nature of the myth and presents possibilities for making this damaging story accessible and meaningful to contemporary queer audiences.

Download free pdf : (insert pdf link here)